Last month, I looked into adaptive trials for individualizing oncology treatment and moving towards personalized medicine. In part 2 of 2 of this series, I’m discussing more specific adaptive clinical trial designs, including umbrella, basket, and N-of-1 trials.

For study sponsors and investigators alike, getting familiar with these adaptive trial designs is important to ensure that the study drug can move through clinical trials and get to the right patients sooner.

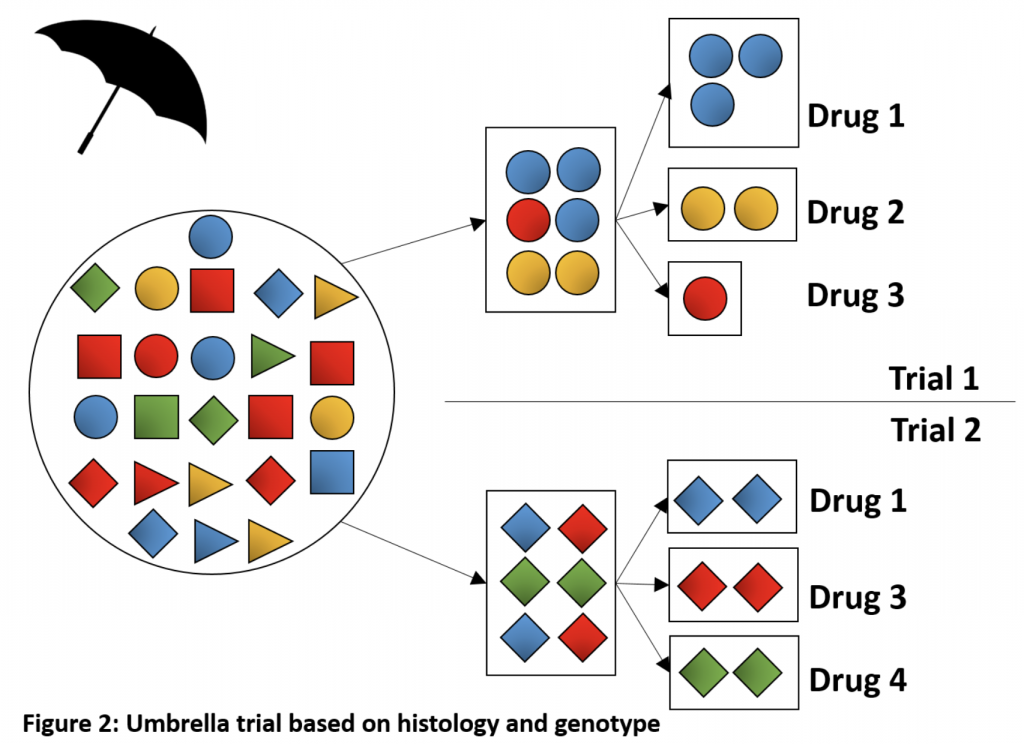

Umbrella Trials

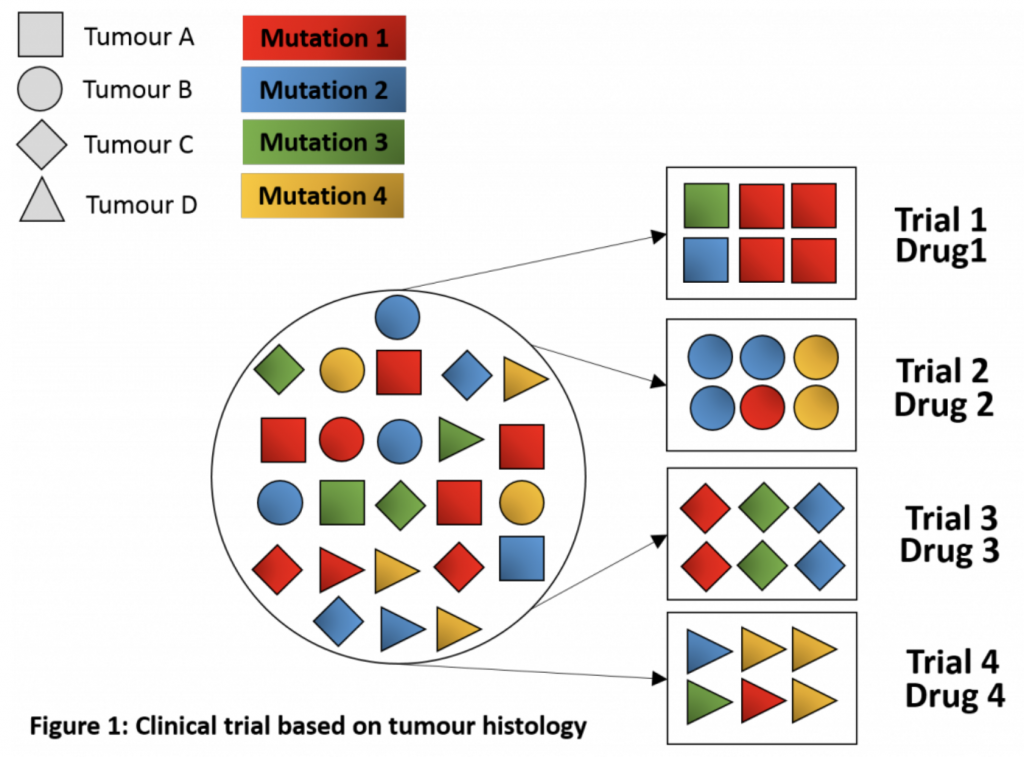

Sometimes also called “platform trials,” umbrella trials usually refer to a trial design that focuses on a single tumor type or histology. However, unlike traditional clinical trials, they comprise multiple sub-trials, each testing a different targeted therapy among patients with a specific mutation or other biomarker.

Umbrella trials are generally performed within a national network of study sites running molecularly targeted clinical trials using the same protocol and a common genomic screening platform. The trial drugs sometimes have different sponsors and may be combination therapies or sequences. Thus, the main rationale for choosing an umbrella trial design is to facilitate screening and accrual of patients. Further, using this adaptive study design allows investigators to add, revise, or drop biomarker sub-trials based on interim data. That is, it allows multiple adaptive enrichment designs within the same protocol, as well as randomized comparisons.

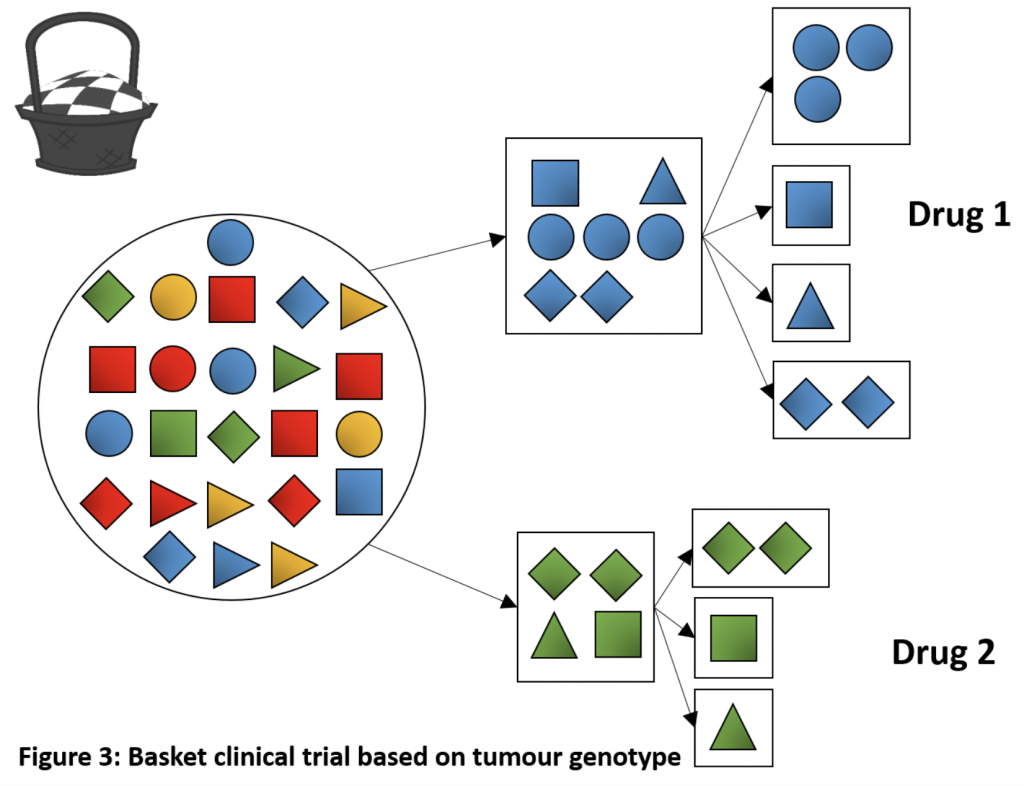

Basket (“Bucket”) Trials

Basket/bucket trials are another type of adaptive clinical trial design. In some ways, they are the opposite of umbrella trials in that they test the efficacy of a single targeted therapy but in multiple tumor types and/or sites. The rationale for using this design is based on the hypothesis that the presence of a molecular biomarker predicts response to the targeted therapy independent of tumor histology or site.

One can consider basket trials as parallel phase II trials for a single drug, but within the same legal entity and on the basis of a common denominator. They are an efficient way to screen experimental drugs across multiple patient populations/cancer types in the early phases of development. It is also a useful design for testing a drug in rare cancers, for which conducting a traditional clinical trial might not be feasible. Basket trials allow separate analyses according to each tumor type/site, as well as for the entire patient cohort. If one patient group shows a good response, this group can be expanded to immediately assess whether others could benefit from the new therapy. If the treatment does not appear to be effective in another group, this group may be closed and the other cohort can continue the recruitment.

Similar to for umbrella trials, a single protocol is generally used for the whole basket trial, irrespective of the tumor types evaluated as part of the trial. Moreover, basket trials may also include a common genetic screening platform.

Logistical and Statistical Challenges of Umbrella and Basket Trials

Umbrella and basket trials utilize an adaptive design to exclude ineffective drugs and/or add new treatment arms based on new knowledge or novel mutations. A major benefit of these trials is that the pre-scheduled interim analyses of the treatment arms allow greater enrolment to the arms performing better.

Umbrella and basket trials utilize an adaptive design to exclude ineffective drugs and/or add new treatment arms based on new knowledge or novel mutations. A major benefit of these trials is that the pre-scheduled interim analyses of the treatment arms allow greater enrolment to the arms performing better.

However, just like the barriers to adaptive trials discussed in part 1, umbrella and basket trials come with their own set of hurdles. Umbrella trials require a large patient sample to identify and enrol enough patients in each treatment arm. Especially, if the mutation of interest is rare, enrolling sufficient numbers of patients into that arm may be challenging. Further, tracking of patients and samples can be complicated and time-consuming for such large, multi-center trials. Ensuring consistent methodology in terms of biopsy methods, molecular assays, laboratory tests, and administration of the study drug is also essential. For these reasons, close collaboration between the investigators at all different sites is key.

The statistical aspect of these trials poses another challenge. For example, can you use a common control arm for all experimental arms? If a patient has not just one, but two or more of the targeted biomarkers, in which arm should they be included? How can you modify the arms during the trial without introducing bias?

In terms of basket trials, the possibility of heterogeneity in the therapy response due to different tumor types must be considered and the trial has to be adapted accordingly. Furthermore, this trial design requires strong biomarkers associated with the drug, especially when rare cancers are included. In other words, for this type of trial to be successful, the tumor must depend on the targeted pathway, and the targeted therapy must reliably inhibit the target.

N-of-1 Trials

Finally, another novel adaptive trial design is N-of-1 trials. Although the concept itself is not new – clinicians often test different drugs and monitor their patients for a response before deciding whether to try a different one or stay on the current drug – formal N-of-1 trials are a fairly recent phenomenon.

Finally, another novel adaptive trial design is N-of-1 trials. Although the concept itself is not new – clinicians often test different drugs and monitor their patients for a response before deciding whether to try a different one or stay on the current drug – formal N-of-1 trials are a fairly recent phenomenon.

In N-of-1 trials, all relevant data are collected from a single patient at regular intervals. These trials can employ the same design and statistical techniques as population-based trials, such as blinding and using the standard of care or a placebo as the control for periods of the study. Using a crossover design, with different therapies given to the same person over time, investigators can compare the effects of different treatments in the same person. This design may be useful for rare cancers, to determine the optimal dose in individual patients, as well as in the early stages of clinical drug development or for exploring the molecular and physiological effects of an existing drug for a new – currently off-label – indication.

Why are These Trials Not More Common?

In theory, if a consistent study design can be applied across multiple N-of-1 studies, researchers should be able to conduct a meta-analysis to draw inferences about the efficacy of an intervention in certain populations. However, to date, the use of N-of-1 trials has been sparse in the clinical trial setting. The reasons for this are somewhat unclear. Among other potential reasons, these trials require a substantial time commitment on both the clinician’s and patient’s part. This is especially true when there is a need for frequent monitoring of the patient. Depending on the condition, digital technologies such as wearables may facilitate the monitoring process.

Similar to other adaptive trial designs, there are also statistical challenges. Especially, there is a risk of carryover effects from one treatment to another when using a crossover design. Of course, the study patient tends to benefit from a trial individualized to their specific needs and characteristics. However, the lack of immediate generalizability of the results to a larger patient population may turn researchers away from this design.

At the end of the day, this type of trial design is not right for everyone. N-of-1 trials are likely the most suitable for chronic conditions with easily measurable endpoints. When using a crossover design, therapies with a short half-life are the most appropriate to minimize the risk of carryover effects. Nevertheless, while there is a need for more individual studies and meta-analyses of the results to determine the usefulness of N-of-1 trials, this design provides study sponsors and investigators with another tool in their arsenal.

How Impetus Can Help

Did you know that the Impetus InSite Platform® can be used to facilitate collaboration between industry and clinical trial investigators at multiple study sites? Further, stakeholders can use the platform to discuss, review, or co-author study protocols and other documents. Online advisory boards are an ideal tool for knowledge-sharing among, and insight-gathering from, investigators, statisticians, clinicians, or patients who have previously worked on adaptive trials. In addition, they are also useful for collecting insights from oncology KOLs regarding their views on evidence from adaptive vs. traditional trials for treatment decision-making. Finally, national or international online learning programs surrounding adaptive trial designs are an impactful and cost-effective way to educate key stakeholders. The possibilities are endless!

References

Azvolinsky, A. (2015). Understanding Umbrella & Basket Trial Design in Lung Cancer. OncoTherapy Network. Retrieved from https://www.oncotherapynetwork.com/lung-cancer-targets/understanding-umbrella-basket-trial-design-lung-cancer

Benner, A., Beisel, C. (2016). Design and Analysis of Umbrella and Basket Trial. Retrieved from https://statmarker.sciencesconf.org/data/pages/Benner_Presentation_STATMAKER_20_10_2016.pdf

Berry, D.A. (2015). The Brave New World of clinical cancer research: Adaptive biomarker‐driven trials integrating clinical practice with clinical research. Mol. Oncol., 9, 951–959.

Dangi-Garimella, S. (2015). New Oncology Clinical Trial Designs: What Works and What Doesn’t? The American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/journals/evidence-based-oncology/2015/the-american-society-of-clinical-oncology-annual-meeting-2015/new-oncology-clinical-trial-designs-what-works-and-what-doesnt

Lillie, E.O., Patay, B., Diamant, J., et al. (2011). The n-of-1 clinical trial: the ultimate strategy for individualizing medicine? Personalized Medicine, 8, 161-173.

Menis, J., Hasan, B., Besse, B. (2014). New clinical research strategies in thoracic oncology: clinical trial design, adaptive, basket and umbrella trials, new end-points and new evaluations of response. European Respiratory Review, 23, 367-378

Redig, A.J., Jänne, P.A. (2015). Basket Trials and the Evolution of Clinical Trial Design in an Era of Genomic Medicine. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33, 975-977

Schork, N.J. (2015). Personalized medicine: Time for one-person trials. Nature, 520, 609–611

Stevenson, D. (2015). Genetic sequencing approaches to cancer clinical trials. BHD Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.bhdsyndrome.org/forum/bhd-research-blog/genetic-sequencing-approaches-to-cancer-clinical-trials/